Fairy stories tell

about ordinary events in extra-ordinary ways. They begin with “Once upon a time…”

and end with “happily ever after;” words that open possibilities, hopes,

dreams, and unleash the imagination. These first and last lines set us up to

believe what we might otherwise consider foolish. The shifts in a fairy story

invite us to be open to the possibility that hovels can become castles, poor

girls can marry the prince, and horrible beasts can turn into handsome

consorts. Prayer is also about shifts in events or people that need to happen

in ways that are sometimes not readily apparent.

We

pray for the fantastic leaps from illness to wellness, from bondage to freedom,

from scarcity to abundance. We visualize connections between polar opposites

and hold together what is split apart as we pray. Like in a fairy tale, the

change we seek is not always the change that takes place. Sometimes, the change

is not in our circumstance but in ourselves; not in the direction we perceive

as best but toward a better or, perhaps, more mysterious resolution. In prayer,

we open ourselves to change and we are changed.

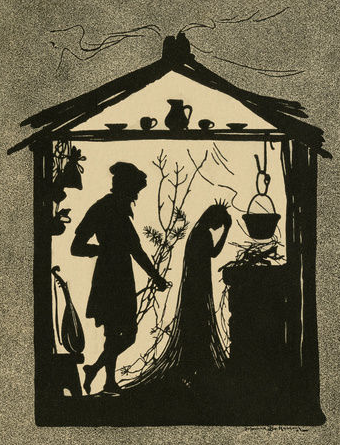

Fairy stories can show us how this change

works. Let’s look at a tale from the Brothers Grimm, “King Thrushbeard” to help

us understand. In this story, a king’s beautiful but proud daughter will not

accept any of the princes who come to court her. None of them is handsome

enough for her. She mocks them, even calling attention to one prince who has a

crooked chin by calling him “King Thrushbeard.” Finally, her father is

exasperated and tells her that as she cannot be satisfied with the royal

suitors, he will marry her to the next beggar who comes to the door. The next

week, a fiddler comes to play beneath the windows of the castle hoping for some

alms. The king invites him in and insists that he marry the princess. They are

wedded on the spot, after which the king declares that as she is now a

beggar-woman, she is no longer welcome in his house and sends her on her way

with the beggar.

She goes away with the fiddler and things

go from bad to worse. She tries to cook dinner and can’t light a fire. She

tries to weave baskets and spin thread but only hurts her hands. She tries to

sell pots in the market and that works well until a soldier rides his horse

through her pots, breaking all of them. Finally, the fiddler/beggar sends her

to work in the king’s kitchen. (The king of that region is Thrushbeard’s

father.) At a wedding banquet prepared for the king’s son, the

princess/beggar-woman escapes from the kitchen to gaze on the festivities. The

king’s son sees her in the doorway and tries to coax her to join the party. She

flees. He follows, catches her and says to her kindly,

“Do not be

afraid, I and the fiddler who has been living with you in that wretched hovel

are one. For love of you I disguised myself so; and I also was the soldier who

rode through your crockery. This was all done to humble your proud spirit, and

to punish you for the insolence with which you mocked me.”

Then she wept

bitterly and said, “I have done great wrong, and am not worthy to be your

wife.” But he said, “Be comforted, the evil days are past; now we

will celebrate our wedding.”

The king’s daughter in

this story is beautiful. We are supposed see something of value in her. But her

character is flawed; she is proud, mean, haughty and uncaring. In the course of

the story, her rejected suitor becomes her savior not because she deserves it,

in fact, she repeatedly proves she does not deserve the kind king, but because

he loves her. He loves her enough to test her and give her opportunity to

change. She can become a beautiful person both inside and out. She

is eventually humbled and confesses herself undeserving of such a kind king.

He, however, has already forgiven her fault. He planned her redemption, hoping

that she would change. In the end, she is clothed in beautiful clothes to match

her beautiful self and celebrates her wedding to this

kindest of kings in royal style.

So, how is this fairy story like prayer?

In prayer we meet ourselves as we are. At the same time, God discovers and

loves us. In prayer we find that the possibility to change lies in us. And we

find that we are able to receive life as it is given not as we suppose it

should be. The king’s beautiful daughter had already imagined a particular kind

of husband. None of her suitors met her very limited expectations. But, in the

end, she was able to see that her standards were far too narrow. A good husband

is much more than handsome. He loves unreservedly. No more mention is made of

his physical deficiency. That has become incidental to his generosity and love.

Like the fairy tale, “King Thrushbeard,” the

parable of the friend at midnight in Luke 11:5-13, tells a story about an unwarranted

change of heart. A man with unexpected guests goes to a friend’s house and asks

for three loaves of bread. Now this number, three, indicates a real need. He

does not just need some bread for back-up. He needs a whole meal; he has

nothing. His friend is his last hope. He begs. His friend is in bed. He

cajoles. His friend is already asleep. He promises. He whines. He invokes all

past favors. His friend finally gets up and gives him bread. Prayer works like

that. It changes intentions, it changes the will, and it softens the heart.

Then comes the fairy tale lesson. “Ask and

you will receive, seek and you will find, knock and the door will be opened.”

Here’s a promise that we don’t take seriously because it

sounds too good to be true, like a fairy tale. It sounds something like “make

three wishes.” We may not understand the full implication of this promise. It

is highly likely that our expectations must be simplified, our detection

purified and our vision clarified. We may not necessarily get what we request.

God is able to do more than you imagine with much less than you hope for. The

promise is that everything that comes from God is good. The “unanswered prayer”

may simply indicate that we are not yet ready for the good gifts God is giving.

Fairy tale prayer is always an opportunity to change in order to receive God’s

goodness. “If you know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more

will God give the Holy Spirit to those who ask?”(Luke 11:13). And the Holy

Spirit at work in us will change us.

Remember the king’s beautiful daughter?

She did not think being married to a poor fiddler was a great idea, but it left

her in a far better situation than she would have chosen for herself. Fairy

tale praying is not for petulant, willful children, but for any childlike

person who says a complete and simple, “yes,” to what God wants to do, who is

willing to be changed and who believes that God is “able to accomplish

abundantly far more than all we can ask or imagine.”

Naomi

R. Wenger, 2019